Native American Heritage Month

Welcome to OrchestraOne’s celebration of Native American art, music and heritage! Below, you will find information, resources and examples of traditional, modern, and contemporary Native American Arts. We are especially excited to announce a partnership with young musicians from the Western CT Youth Orchestra, who have volunteered their time and knowledge to contribute to this page. Click HERE to see their contribution below!

A quick overview...

· At some point between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago, the first peoples to inhabit the Americas crossed over the Beringia land bridge from present day Siberia to Alaska, spreading throughout the entirety of the Americas from the Arctic to Argentina. In what we now know as the United States, ethnographers frequently divide the area into 8 regions: Northeastern Woodlands, Southeastern Woodlands, Great Plains, Great Basin, Northwest Plateau, Northwest Coast, California, and Southwest. Within these broad swaths of land, there lived between 10 and 18 million peoples living within 600 tribes, over 500 of which remain active today. Given the incredible richness, endlessly diverse and infinite knowledge both ancient and modern exemplified by these 600 tribes, all of which had slightly (and sometimes drastically) different traditions and cultures, we strive to provide a cross section of the art and music of Native Peoples in present-day United States from the Pre-Columbian Era until today. Please note however, that this page is only the tip of the iceberg, and resources will be provided below to dig even further into these meaningful areas. Enjoy!

Native American Art

While every tribe had (and continues to have) subtle and unique artistic tendencies and ideals, they all share a few characteristics. First, Native Americans, as with many indigenous cultures, do not view art in the same way as, for example, Western Europeans.

Art within Native American culture is approached holistically and is interwoven throughout their lives in conjunction with spirituality, function, ritual and daily life, both social and personal. For example, many folk and indigenous songs around the world were written to accompany particular events, rituals, rites and dances. The same is true for artistic objects within Native American tribes – even objects whose function was simply to carry things were made to have great beauty, spurring an emotional response in its viewer just as a Rodin sculpture does in the Metropolitan Museum.

Socorro black-on-white storage jar. ca. 1050–1100 - Ancestral Pueblo, On view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Apache storage Basket, made from Willow shoots, devil's claw, and yucca root.

Basket weaving is one of the oldest traditional Native American crafts. The earliest evidence of these baskets is from around 8,000 years ago, and each community had their own ways to weave. Material varied from sweetgrass, to tree bark, pine needles, and even porcupine quills. The intricacy and beauty of these works of art along with the great skill it took to make these baskets made them highly desirable objects in the mid-1800s, and the craft is still alive and thriving today. For more about the function and techniques in Native American basketry, click HERE for a great interactive article.

One example of art being used spiritual practices is transformational masks, most commonly used by tribes of the Northwest Coast. The masks depict an animal on its outer shell that can be pulled back to reveal the face of a human. During rituals, this symbolizes the wearer’s transition and connection to the spiritual realm.

Namgis first Nation (present day Vancouver Island(. Thunderbird Transformation Mask, 19th century. Cedar, pigment, leather, nails, metal plate, on view at the Brooklyn Museum.

As mentioned before, art in Native American cultures is viewed in a holistic way, blending and mixing the worlds between function and beauty. This extended to almost every aspect of daily life, including that of music-making. Instruments were dictated and made with materials found in the areas they lived, not unlike most indigenous cultures. The most common instruments in Native American tribes in the present United States are rattles, drums, flutes and whistles. Among these instruments, there is endless variation in size, ritual purpose, sound and material. Below is a cross-section of some of these instruments.

Ravel rattle (Tsimshian)

Chegah-Skah-Hdah (dance wand) - (Sioux)

Tsii'Edo'a'tl (fiddle) - Athabascan Family - There is some debate as to how much European influence this instrument has

Wakan-chan-cha-gha (frame drum) Sioux or Dakota tribe

Pib-be-gwun or Siyontanka - (Chippewa or Ojibwa)

Drum - (Creek, Muskhogean family)

Shak Shak (Guyanese)

Visual art from Native American communities is an area of immense wealth and meaning – from baskets to clothes, totem poles, wampum belts, moccasins, cave paintings, canoes, effigies, sculptures, carved turtle shells, pottery, weapons, shields, blankets and countless more. Art is imbued in all of these. With the unending small and large variations between tribes, and artistic evolution over thousands of years, Native American art is a source of infinite inspiration.

Native American Music

Like visual art, specific musical styles varied from region to region, but in general, Native American Music consisted mostly of voice with accompaniment by drums, rattles and other percussion instruments. Music was used in countless ceremonies and rituals, accompanied daily tasks, used for teaching, and otherwise permeated life within the tribe.

As Bruno Nettle says, “human beings were not considered to be the active originators of music, but rather the recipients of music imparted to the tribe by spirit beings, either through dreams and visitations or, more directly, at the legendary time of the tribe’s origin.”

Apache sunrise song

Music has an especially deep connection to the spiritual, as it is generally believed that the ability to create music is a gift from the spiritual realm. So much so that when a singer would invent a new melody, it was not generally thought that the music came from that person alone, but that it came from a spiritual being, communicating the melody through the singer.

Prayer song with call and response

Vocal styles, rhythms and text varied between tribes and regions, but there are some characteristics that tie these styles together: call and response is prevalent; the songs frequently used vocables, or syllables that have no lexical meaning; instrumentation was frequently kept to voice, percussion and occasionally flute/fiddle; melodies were typically kept within a 4-6 note scale; music was frequently accompanied by dance, or had some other activity associated with it such as a medicine ceremony or marriage.

One aspect of this music-making that can be used to differentiate between tribes is the timbre and range of the voice. Compare this Sioux chant with the prayer song and Apache sunrise song above, and see what kinds of differences there are in style and sound.

Sioux tribal chants

Native American poetry is a wonderful example of how music reached every corner of life. Native American poetry was usually, if not always, sung. In fact, many scholars say that it is better to call Native American poems “songs” instead of poems.

As Agnes Grant says, “[poetry] played a role unequalled by poetry in Western society; the religious and artistic preoccupation of much of the Indian world went far beyond anything in the European experience…it was much more an integral part of everyday life. It was not a thing set apart for enjoyment or entertainment. The composition and singing of songs was a most important occupation.”

The Tatanka Oyate Singers

While much of Native American music consisted of vocables, poetry/song had texts, frequently used in the oral tradition to pass down creation stories, teach children various tasks, to accompany ceremonies, and to be sung at particular times of the day/year. Below are some examples of this poetic text.

Dream Song (Chippewa)

In the Sky

I am walking A Bird

I accompany.

This particular song was sung by Owl Woman, A medicine woman of the Papago tribe

Medicine Song (Papago)

How shall I begin my songs

In the blue night that is settling?

In the great night my heart will go out,

Toward me the darkness comes rattling,

In the great night my heart will go out

Cree love song:

Love Song (Cree)

I wonder if she only looks out Near to weeping, my sweetheart and says,

"Ah me, my sweetheart I love him".

Katherine Mombo, Assistant Concertmaster at the WCYO

As part of a partnership with the Western Connecticut Youth Orchestra (WCYO), this next section is brought to us by Katherine Mombo, a talented high school violinist and Assistant Concertmaster with the WCYO Symphony Orchestra. We are so grateful to Katherine for volunteering her time to explore these rich traditions! Without further ado, here is Katherine’s work on ceremonial music in Native American tribal cultures.

Music is a valuable and sacred part of Native American ceremonies. It is an integral component of gatherings that commemorate life, hunting, healing and renewal. Ceremonial music typically consists of vocals and drums. The most common form is called song cycle. The cycle begins with a leader who opens by singing a simple melody. A chorus will then repeat that melody with a variety of rhythms and pitches.

This call-and-response style can be observed throughout many Native American songs, prayers, and chants. Drums and rattles are often used to accompany the voices. Indigenous people used this music style for both secular music and cherished ceremonies.

A traditional prayer song. Notice how the chorus echos the phrases after it is sung by a single voice.

Here is an example of music that would be played during the Green Corn Dance in the Seminole Tribe. (music starts at 0:35)

One cherished event is the Green Corn Ceremony. Celebrated annually by Southeastern Native American tribes, it recognizes corn harvest of the New Year. Corn was one of their most important staple foods, so this ceremony was a time for Native Americans to express their gratitude for the crop. The festival, which lasts 4-8 days consists of cleaning, dancing, and music.

The Sun Dance is another core ceremony in the Plains Native American regions. It is a time that celebrates the sun’s role in providing life to the things of Earth. Additionally, those who participate have personal wishes which commonly include good health for their family, hunting skills, or spiritual insight. The ceremony consists of several days of dancing, fasting, sacrifice, and music.

This is an example of a sun dance song from the Arapaho tribe.

Thank you Katherine for that wonderful contribution!

Next, we are going to explore post-Columbian traditions, modern/contemporary musicians and composers, and the enormous influence Native American music has had on American Classical music in general.

Thunder Hill Singers - Contest Song - (Honor Song 2) Choctaw PowWow 2015

First, it’s important to note that many tribes are keeping the traditional way of singing alive today. Around the country, there are ceremonies, festivals and “sings” (such as the Choctaw PowWow, shown here) that celebrate these communal acts.

These gatherings have helped to spur a recognition of the importance of this music, as younger generations become more involved in traditional music making. This video here is a fantastic example of how one can differentiate between tribes by the range of voice used. Compare this video of a Cree song to the Choctaw song just above.

Northern Cree @ Mandaree 2015. SNL drum solo contest

While we will focus on the works and performance of peoples of Native American descent, it is also important to note that Native American Music had an enormous influence on composers in present day United States and the world, dating back to the 18th century. In fact, the fascination of Native American melodies in particular spurred an entire movement in American Classical Music called the “Indianist” movement, led by composers like Charles Wakefield Cadman, Arthur Farwell, Charles Sanford Skilton, and Arthur Nevin. Perhaps most famously, the Czech Composer Antonin Dvorak was heavily influenced by this music, as was British composer Samuel Coleridge Taylor. Composers were not only inspired by the music itself, but by the legends and creation stories held dear by Native American Cultures.

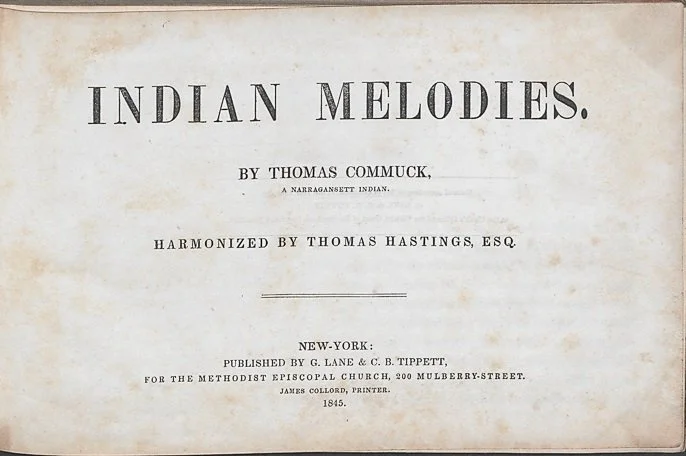

One interesting bit of history that shows the confluence of Native and non-Native American cultures is Thomas Commuck’s Indian Melodies book. This is widely thought to be the first published musical work by a Native American. A member of the Narragansset Tribe, Commuck collected various melodies from many tribes, translated them into contemporary, had it harmonized in Western Classical language, and included Christian religious themes. The entirety of the book can be found here.

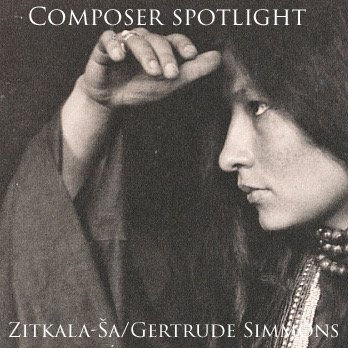

Native American composers were few in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but one who has unending influence is Zitkala-Sa. A violinist, composer, activist and writer, Zitkala-Sa (aka Gertrude Simmons) lived a remarkable life, and was dedicated to not only preserving Native American traditions, but bringing them to the rest of the world to be honored and respected. Her most well known Musical Work, the Sun Dance Opera remains one of the seminal works by a Native American composer. OrchestraOne did a special composer spotlight on her and it can be found, HERE.

Louis Ballard (Quapaw name, Honganozhe, 1931-2007) is known as the “father of Native American Composition.” Having gone to school at the Seneca Indian Training School - a school that he believed was used to brainwash Native American children of their roots - Ballard went on to study composition at some of the finest festivals such as the Aspen Music Festival, and with well-known composers like Darius Milhaud.

Louis Ballard: Four American Indian Piano Preludes, Emanuele Arciuli, piano

This quote by Ballard exemplifies his beliefs: "It is not enough to acknowledge that Native American Indian music is merely different from other music. What is needed in America is an awakening and reorienting of our total spiritual and cultural perspectives to embrace, understand, and learn from the Aboriginal American and what motivates his musical and artistic impulses."

Even after being ridiculed and excluded by his peers and teachers for his heritage, Louis Ballard never lost sight of his roots, and was an active member of his tribal community. While his music is within a Western Classical Style, it is all firmly rooted in traditional Native American Music.

Composed by Louis W Ballard (1931-2007) and performed by Dana Winograd, cello and Ivan Koska piano.

One of the most well known performers of Traditional Native American Music is Raymond Carlos Nakai (b. 1946, Ute/Navajo Heritage). At first a trumpet player (even playing in the US Navy Band), an accident left him unable to play, eventually leading him to the cedar flute, among other traditional instruments.

Native Flute Solo - R. Carlos Nakai, Live at Montgomery College

Nakai has been nominated 11 times for Grammys and has collaborated with some of the 20th century most well-known composers like the minimalist, Philip Glass. Much of his music is improvisational, as he says: “I build upon the tribal context, while still retaining its essence. Much of what I do builds upon and expresses the environment and experience that I’m having at the moment.”

Brent Michael Davids (b. 1959, Stockbridge Munsee) Is one of the most well-known Native American Composers alive today. He has written for ensembles such as the National Symphony Orchestra, the Kronos Quartet, and the Joffrey Ballet

Brent Michael Davids, Sanctus: Singing for Power from Requiem for America. Performed by UW-Whitewater Chamber Singers and Medicine Bear Singers Robert Gehrenbeck, conductor

Another choral work of his, Singing for Water tells the story of Native Americans protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2017, recreating elements of the experience alongside the narration.

Like Ballards music, David’s Music is strongly rooted in traditional native themes, and is incorporated in an even more pronounced way. In his, Sanctus: Singing for Power from the Requiem for America, he places the Medicine Bear Singers (a traditional Native American Singing Group) directly next to a Western Classical Style Choir.

Singing for Water, by Brent Michael Davids. Performed by the University of Wisconsin Choirs. Robert Gehrenbeck, Conductor.

Brent Michael Davids is also dedicated to encouraging and supporting other Native American Composers. He was an integral figure in the creation of the First Nations Composer Initiative (FNCI), and CANOE (Composer Apprentice National Outreach Endeavor), which places American Indian composers in residency to teach American Indian high school students.

Another towering Native American composer is Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate (b. 1968, Chickasaw). As a pianist and composer, he has been commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra, Buffalo Philharmonic, Detroit Symphony and the San Francisco Symphony among others. Currently, he teaches composition at Oklahoma State University.

Having been inspired by Bella Bartok, one of the first composers to recognize the folk music of his own heritage and land, Tate says: "I didn't mix my identities of being a classically trained musician and being an American Indian. I never saw that there was even a possible relationship between those two until I started composing. And that's when they came together in a way that made me feel just wonderful."

Shakamaxon: I. Remembrance by Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate - Carnegie Mellon University Contemporary Music Ensemble, conducted by Daniel Nesta Curtis.

Pisachi (Reveal) performed by ETHEL

Tate’s music is similar to the music of the composers above in that it incorporates traditional Native American elements, ideas and sometimes instruments, but differs a bit in its incorporation into a more Western-Contemporary Musical Aesthetic. This is exemplified in Shakamaxon, named after a historic Lenape Indian village that bordered the current city of Philadelphia.

One of the more experimental composers of Native American heritage is Raven Chacon (b. 1977, Diné). Having won a plethora of awards from around the world, he currently serves as the Composer-in-Residence at the Native American Composers Apprenticeship Project.

Raven Chacon | American Ledger (No. 1) - UBC Symphonic Wind Ensemble | Robert Taylor, conductor

Chacon’s music is both aurally and visually stimulating. It engages all of the senses and broadens the idea of what an instrument can be, while still connecting emotionally with its listeners.

To say that Native American art and music is vast would be an incredible understatement. It is an endlessly rich and meaningful area of study that has influenced every part of what we now call American Art. We hope this page has given you valuable insight into these art forms and see below for sources to continue with your own research!

Sources

Nettl, Bruno. “North American Indian Musical Styles.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 67, no. 266, University of Illinois Press, 1954, pp. 351–68, https://doi.org/10.2307/536412.

Levine, Victoria (1998). American Indian musics, past and present. In D. Nicholls (Ed.), The Cambridge History of American Music (The Cambridge History of Music, pp. 1-29). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521454292.002

TraditIONAL NATIVE POETRY AGNES GRANT,

Department of Native Studies, Brandon University,

Brandon, Manitoba,

Canada, R7A 6A9.

http://www3.brandonu.ca/cjns/5.1/grant.pdf

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Sun Dance". Encyclopedia Britannica, 8 Jan. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sun-Dance. Accessed 15 April 2021.

Densmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

https://oneida-nsn.gov/dl-file.php?file=2016/04/IROQUOIS-TRADITIONAL-CEREMONIES-8.17.pdf

Iroquois Midwinter Ceremony. (n.d.) Holiday Symbols and Customs, 4th ed.. (2009). Retrieved April 15 2021 from https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Iroquois+Midwinter+Ceremony